Following my recent (and first) trip to Disneyland, I delved into Richard Snow’s book, Disney’s Land, which chronicles the park's history. Early in the text, Snow recounts a story I hadn't previously encountered, and it captivated me—not only for its specifics but also, as I will explain soon, for its potential relevance to today's circumstances.

The narrative begins in 1948. Snow mentions that Disney’s personal nurse and informal confidante, Hazel George, grew concerned. “[She] began to sense that her boss was sinking into what seemed to her to be a dangerous depression,” Snow writes. “Perhaps even heading toward what was then called a nervous breakdown.”

The reasons for this distress were clear. Disney's studio had not seen a successful release since Bambi in 1942, and the war had caused the loss of European markets, coupled with the economic instability that followed, placing a strain on the company's finances. During this same timeframe, Disney faced an animator's strike, which he perceived as a personal betrayal. “It seemed again to just be pound, pound, pound,” Snow notes. “Disney was often aggressive, abrupt, and when not angry, remote.”

Hazel George, however, had a remedy. Aware of Disney's childhood love for steam trains, she became intrigued when she spotted an advertisement for the Chicago Railroad Fair, which showcased exhibits from thirty railway lines across fifty acres by Lake Michigan. She proposed that Disney take a trip to see the fair, and he embraced the idea.

In Chicago, captivated by what he saw, Disney experienced a resurgence of the creative passion that had been absent during the war years. He just needed to find a way to channel it. By chance, upon returning to Los Angeles, one of his animators, Ward Kimball, introduced him to a group of West Coast train enthusiasts who were building large-scale models of functioning steam trains that adults could ride on (approximately the size of a child’s wagon).

Disney decided this was what he needed to pursue.

In 1949, he and his wife, Lillian, acquired a five-acre tract on Carolwood Drive in the Holmby Hills area of LA to construct a new home. They selected this site partly due to Disney’s belief that its layout was ideal for his scale railroad project.

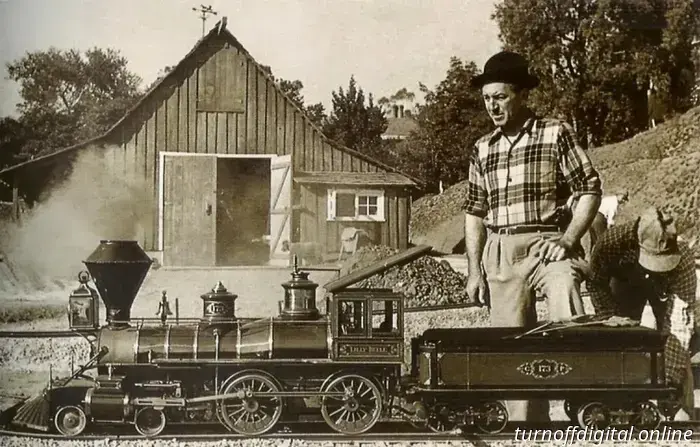

Over the following year, he collaborated with the machine shops at his studio to build his scale trains and worked with a team of landscapers to develop the track and its surroundings. When completed, Disney’s Carolwood Pacific Railroad, as he named it, comprised a half-mile loop that encircled the house and yard, including a 46-foot-long trestle bridge and a 90-foot-long tunnel dug beneath his wife’s flower bed—designed with an S-turn so that the other end was hidden from view upon entry. His collection included a 1:8 scale steam locomotive dubbed the Lilly Belle, six cast-metal gondolas, two boxcars, two stock cars, a flatcar, and a wooden caboose intricately decorated with miniature details like a broom-sized twig and a tiny potbelly stove that could actually be lit.

As Snow narrates, this endeavor revitalized Disney. The more he worked on the railroad, the more ideas began to surface for his company. Soon, one idea started to overshadow all others. In 1953, Disney abruptly ceased operations on the Carolwood Pacific. It had fulfilled its purpose of rekindling his creative spark, but he now had a larger project to tackle—one that would dominate the latter part of his career and provide him with endless fascination and enthusiasm: the creation of a theme park.

As Snow summarizes: “Of all the influences that helped shape Disneyland, the railroad is the seminal one. Or, rather, a railroad. One Disney owned.”

~~~

I term what Disney achieved in creating the Carolwood Pacific Railroad as engineered wonder. More broadly, engineered wonder refers to the pursuit of something that ignites a genuine interest, to an extraordinary degree (or, depending on perspective, perhaps even to the point of absurdity). Such endeavors are not motivated by profit, advancement, or recognition, but rather by the sheer fascination they evoke, and the desire to amplify that feeling as much as possible.

This leads me back to the connection I promised to our current moment. In the early 1950s, Disney utilized engineered wonder to escape the creativity-draining economic stagnation caused by wartime uncertainty. Seventy-five years later, I see a broader relevance for this approach: escaping the digital stagnation created by mediating too many of our experiences through screens.

I increasingly worry that as we conduct more of our personal and professional lives in the indistinct realm of the digital, we become disconnected from the authentic joys and challenges of the real world: to truly feel awe, curiosity, or fascination—not merely an algorithmically-optimized emotional response; to witness our intentions manifested concretely in the world,

Following my recent (and first) trip to Disneyland, I delved into Richard Snow’s history of the park, titled Disney's Land. Early in the book, ...