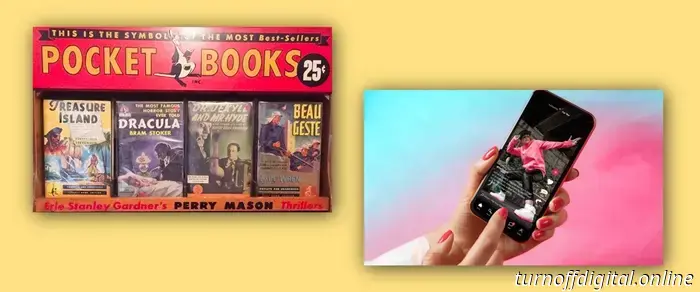

In 1939, Simon & Schuster transformed the American publishing landscape with the introduction of Pocket Books, a series of small books (4 by 6 inches) priced at just a quarter—an impressive bargain during an era when a regular hardcover could cost between $2.50 and $3.00.

To ensure the financial viability of this model, Simon & Schuster needed to sell a large quantity of books. “They sold books in places they had never been before—grocery stores, drugstores, and airport terminals,” Clive Thompson notes in a compelling 2013 article about the Pocket Books trend. “Within two years, they had sold 17 million.” Thompson references historian Kenneth C. Davis, who reveals that these new paperbacks had “tapped into a vast reservoir of Americans who nobody realized wanted to read.”

However, this demand posed a challenge: there weren't enough books available. In 1939, the book market was relatively small, with Thompson estimating that America had only around 500 bookstores, primarily situated in a handful of major cities. To profit from paperbacks, the yearly influx of new titles would have to increase significantly, necessitating a relaxed approach to what could be published, which led to a sudden emphasis on genre fiction writers capable of producing marketable works quickly.

Interestingly, among this new wave of writers was a young Michael Crichton, who published extravagant paperback adventure novels under pseudonyms during his Harvard medical school years in the 1960s, completing them at a “furious pace” on weekends and holidays. Some of these early works are largely mediocre, but that wasn’t an issue; the aim for many of these paperbacks was simply to provide light entertainment.

The rise of these lower-quality genres, understandably, worried the elite. Thompson quotes social critic Harvey Swados, who characterized the paperback revolution as ushering in a “flood of trash” that would “further debase popular taste.” There was a concern that the mass appeal of these inexpensive books would eventually push out the more serious hardcover titles that had long characterized publishing.

This situation parallels our current reality. As the platforms of the digital attention economy shift from social networking to delivering increasingly distracting short-form videos, the quality of online content seems to be declining into what is often dismissed as slop. Many now worry about who would choose to listen to a podcast or read a lengthy essay when platforms like Sora offer endless videos of historical figures dancing and X presents a continuous stream of nudity and bar fights.

However, revisiting the paperback example might provide a glimmer of hope. Ultimately, the surge in these cheaper, often lower-quality books did not eliminate more serious titles; in fact, quite the opposite occurred. Today, substantially more hardcover books are published than before the Pocket Books revolution.

A closer examination shows that the expansion of the market for published works through paperbacks also significantly increased opportunities to earn a living from serious writing (which, for this discussion, I’ll define as books that take at least a year to write and are published in hardcover). Certainly, there was a lot of mediocre content produced during the paperback boom, but this redefined publishing landscape also created a profitable secondary market for more traditional authors.

For instance, Stephen King sold the hardcover rights to his first novel, *Carrie*, for about $2,500 in 1973 (equivalent to $18,000 today). While this was a decent sum, it was hardly sufficient to live on. Conversely, the paperback rights for *Carrie* sold for $400,000 (nearly $3,000,000 in today’s dollars), allowing King to leave his day job and become a full-time writer.

King was not alone; other esteemed authors, like Ursula K. Le Guin, Ray Bradbury, and Agatha Christie, would likely not have achieved their status without the opportunities made possible by the paperback market. As for Crichton, his nine largely formulaic paperbacks written under pseudonyms helped him hone his skills. His first hardcover, *The Andromeda Strain*, became a huge success and marked the beginning of his influential writing career.

While I harbor a strong dislike for much of the current digital attention economy and believe most people should be engaging with these products far less, I find some comfort in the narrative of paperback books. The rising popularity of a particular type of low-quality media does not necessarily mean that more substantial alternatives will falter. Over one billion TikTok videos will be accessed today, yet here you are, reading a thoughtful essay on media economics. I do not take that for granted.

In 1939, Simon & Schuster transformed the American publishing landscape by introducing Pocket Books, a series of small-sized books (measuring 4 by 6 ... Read more